Tŝilhqot’in History: The Chilcotin War of 1864

Land & Waters of the Tŝilhqot’in

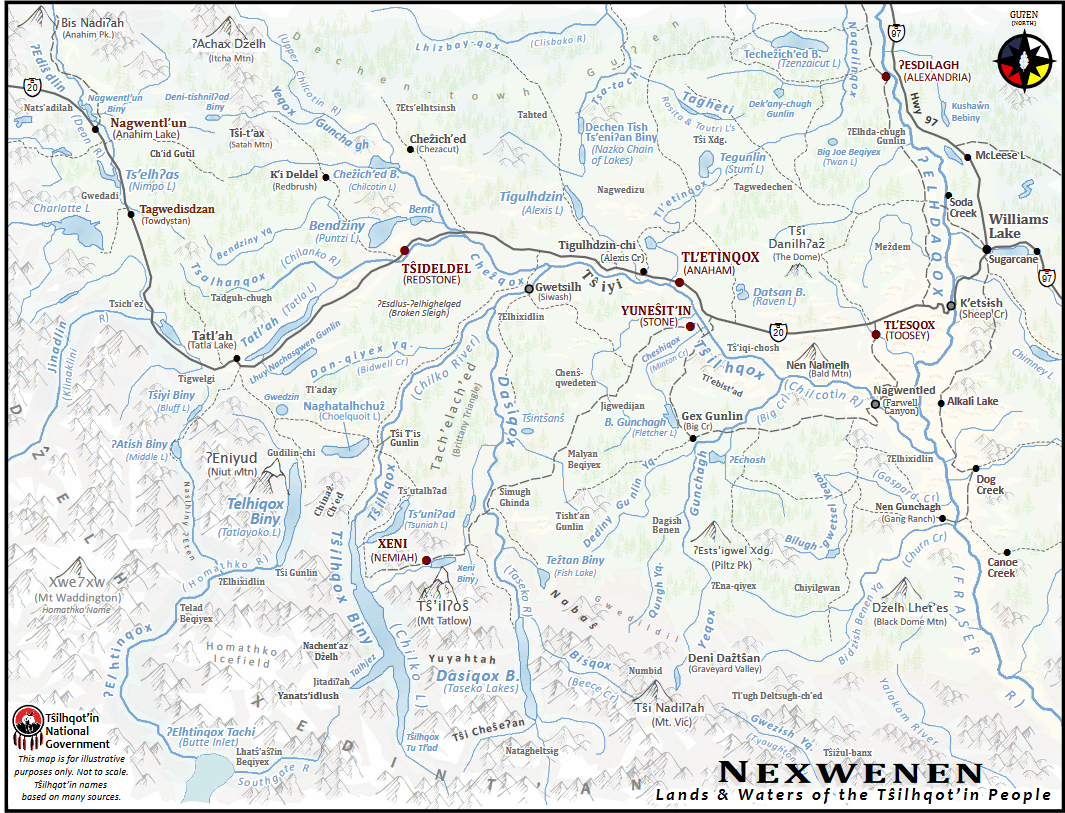

The Tŝilhqot’in National Government is the governing body for the Tŝilhqot’in people. The Tŝilhqot’in Nation is comprised of six communities located throughout the Tŝilhqot’in (Chilcotin) territory, including the Tl’etinqox, ʔEsdilagh, Yuneŝit’in, Tŝideldel, Tl’esqox and Xeni Gwet’in. The communities work as a Nation to continue the fight of our six war Chiefs of 1864. The war Chiefs stood against the Canadian Government in an effort to gain Tŝilhqot’in Aboriginal Rights and Title to the lands we call Tŝilhqot’in.

The Tŝilhqot’in Nation Has Never Surrendered Or Ceded Their Lands.

Taking a Stand in 1864

From a time before the founding of the Province of British Columbia, the Tsilhqot’in people have steadfastly protected their lands, culture, way of life including the need to protect the women and children from external threats – often at great sacrifice. The events of the Chilcotin War of 1864 exemplify the fortitude and the unwavering resistance that defines Tsilhqot’in identity to this very day.

When the Colony of British Columbia was established in 1858, the Tsilhqot’in people continued to govern and occupy their lands according to their own laws, without interference, and with minimal contact with Europeans. However, the Colonial government encouraged European settlement and opened lands in Tsilhqot'in territory for pre-emption by settlers without notice to the Tsilhqot’in or any efforts at diplomacy or treaty-making.

In 1861, settlers began to pursue plans for a road from Bute Inlet through Tsilhqot’in territory, to access the new Cariboo gold fields. At the same time, Tsilhqot’in relations with settlers became strained from the outset, as waves of smallpox decimated Tsilhqot’in populations (along with other First Nations along the coast and into the interior). Between June of 1862 and January 1863, travellers estimated that over 70 percent of all Tsilhqot’in died of smallpox.

Some Tsilhqot’in initially worked on the road crew at Bute Inlet, but the unauthorized entry into Tsilhqot’in territory, without compensation, and numerous other offences by the road crew soon escalated the situation. Tsilhqot’in women and children were disrespected and abused, labourers were refused food, and demands by the Tsilhqot’in for payment for entry into Tsilhqot’in territory were denied. In a pivotal encounter, a road-builder accused the Tsilhqot’in crew of theft, to which they answered, “you are in our country and you owe us bread.” In response, the road-builder wrote down the names of the Tsilhqot’in in a book and threatened to eliminate them with smallpox. In the wake of the smallpox epidemics only months before – decimating over two-thirds of the Tsilhqot’in population, this threat was taken very seriously. The Tsilhqot’in Nation declared war in defense of their territory and people.

“We meant war, not murder.”

One of the Largest Mass extinctions in Canadian History

General area of dispute in 1864 where the proposed Bute Inlet Road was being built.

Customary to Tsilhqot’in culture, the war group covered their faces in war paint, dancing and drumming in an all-night ceremony. At dawn on April 30, 1864, the group of Tsilhqot’in warriors was led by a strong Tsilhqot’in leader named Lhats’as?in (Also referred to as Klatassine/ Klatsassan).

The group attacked and killed most of the men comprising the main and advance camps of the road crew, effectively ending the incursion into Tsilhqot’in territory and the threats of smallpox and abuse. The Tsilhqot’in party suffered no casualties.

Over the ensuing days, the Tsilhqot’in warriors effectively removed all settlers from their lands, forcibly and by death if warnings went unheeded. By June 1864, the road project was abandoned and there was no settler activity between the Pacific Ocean and the Fraser River, a span of 400 km. Meanwhile, Colonial authorities launched what the new Governor called “an invasion” of two militia groups, about 150 men. The two militias wandered without success through Tsilhqot’in territory, unable to engage or locate the Tsilhqot’in war parties in territory that was unknown to them but intimately known to the Tsilhqot’in.

Lhats’as?in (Also referred to as Klatassine/Klatsassan) - One of the Tsilhqot’in Leaders who was hung in 1864, drawn by the missionary Robert Christopher Lundin Brown - 1873.

Frustrated and desperate, the militia threatened the Tsilhqot'in with extermination, burned homes at Puntzi and Sutless (Nimpo Lake), destroyed fishing equipment and attempted to hinder food gathering. The militia's only casualty was a former H.B.C. trader regarded as a leader of those who disrespected the Tsilhqot'in. The Tsilhqot’in lured him into an ambush for execution.

On July 20th, unable to persuade any Tsilhqot'in to betray the war party and out of rations, the Governor made plans to withdraw in defeat. That afternoon, a Tsilhqot'in diplomatic party came to his camp. This, finally, was the first ever meeting between Tsilhqot'in and Colonial representatives. In the ensuing negotiations, Colonial officials promised a peace accord under a flag of truce. However, when Lhats’as?in and seven others came unarmed for this discussion of peace on August 15, 1864, the Governor was not there. To their surprise they were shackled and tried for murder. Lhats’as?in's final comment about these trials was that “We meant war, not murder.”

When the Colony martyred five of “the Chilcotin Chiefs” on October 26, 1864 this was one of the largest mass executions in Canadian history. The executed included Lhats’as?in (Klatsassan/Klatassine), a chief named Tellot, and four others named Tahpitt, Piell and Chessus. A mostly First Nations crowd of 250 people bore witness to the hangings. In the spring of 1865 the officials ambushed Ahan, the Tsilhqot’in headman from Sutless, as he was on his way to pay reparations for any harm to innocents as a result of the Chilcotin War. After a short trial, Ahan, was hanged July 18, 1865 in New Westminister.

Many of those who survived the smallpox epidemics or participated in “The Chilcotin War” went on to have long lives and large families with many of the Tsilhqot'in today counting them as ancestors.

Although an apology was issued by the Attorney General of British Columbia, Honourable Colin Gabelman, in 1993 for the wrongs done to the Tsilhqot’in before and after the Chilcotin War, the false promise of a truce by British Columbia weighed heavily on the Tsilhqot’in. The Tsilhqot’in Nation and their communities were left to continue their fights toward repatriation of their Aboriginal Title Lands until formal apologies and ceremonies marking the injustices suffered by their people were to come years later, almost at the start of the new millenium.